Anatomy and Art: Medieval Mess to Renaissance Revolution

Is your anatomy diagram better than a 1st grader?

In the previous post, we followed Renaissance art as economic forces encouraged art to shift from treating the human body as a religious object to an object of the natural world. Today, we’ll explore how this shifting artistic approach changed anatomy and jumpstarted modern medicine.

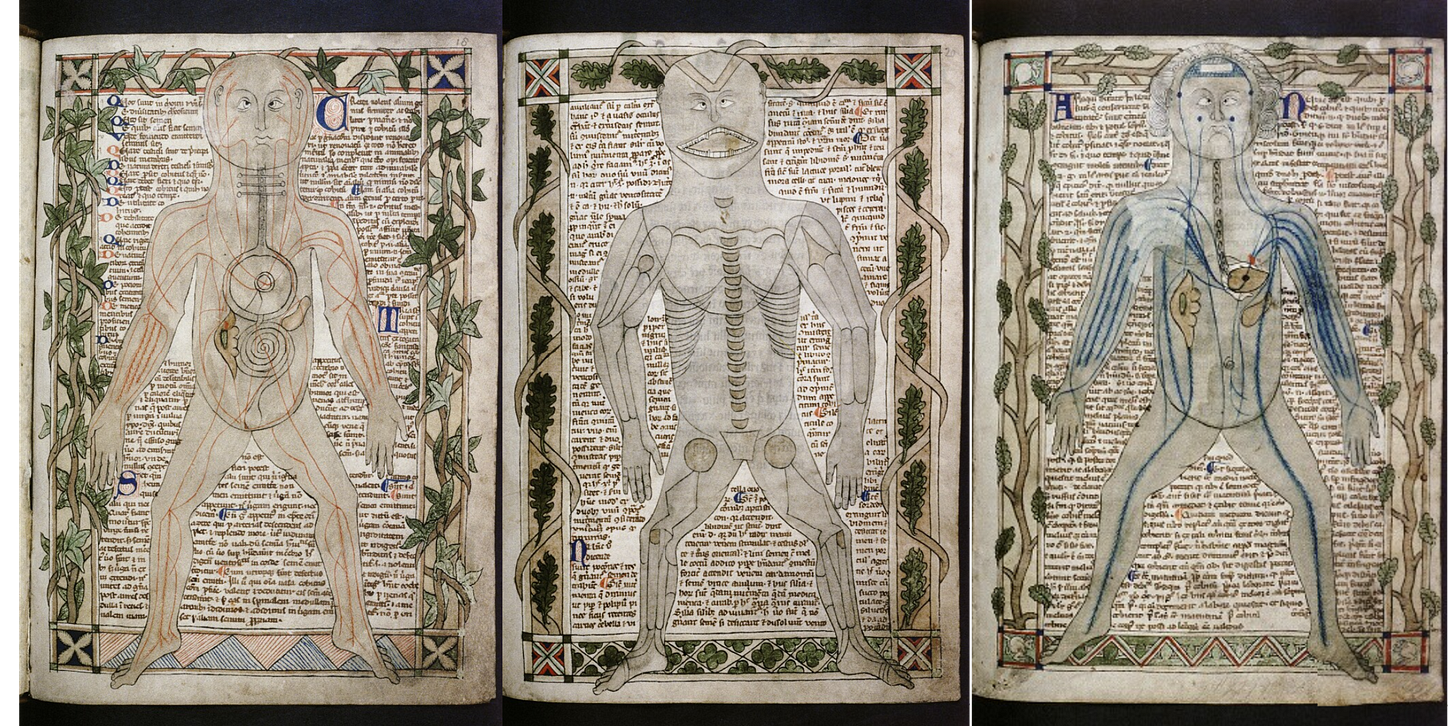

Considering our own bodies have been available for study since the dawn of rational thought, it may be surprising that Medieval understanding of anatomy was terrible. Yet, examine these 13th century medical diagrams:

Why are important anatomy texts from this period only nominally better than drawings by 1st graders? First, without the printing press, most anatomy texts were created by “copyists.” These individuals were devoted to re-creating the text, usually with no practical knowledge of the science of the material. Errors or shortcomings could be cheerfully replicated. More importantly, Medieval medicine was based on historical and religious beliefs. Anatomy knowledge and medical practice rested on beliefs of the “four humors” in the body, laid out a thousand years earlier by the Greek physician Galen. The idea that the body was holy meant that realistic observation and study were less important than religious understandings of its workings.

Additionally, medicine’s practical component, surgery, remained separated from its theory. Doctors were few and only based in universities or noble families. Paris, a major center of learning and commerce since the founding of the University of Paris 100 years earlier, could only boast a handful of physicians during the 13th century. Instead, most medical treatment was performed by “barber-surgeons,” whose role was more understood as manual labor. Their primary services were bloodletting, cutting out malignant growths, or simply cutting off limbs, thus their other moniker, “sawbones.” To amputate a leg, nonrealistic anatomy depictions of man’s inner workings are more than sufficient!

With the birth of the Renaissance, artists became intensely focused on accurate portrayals of the human body based on nature. Religion still determined artistic subjects, but Leonardo DaVinci wrote the purpose of art was to paint ‘man and the intention of his soul’ in terms of the ‘attitudes and movements of the limbs.’[2] Art became connected to observational study of the physical world—anatomy even became part of an artist’s apprenticeship training. DaVinci himself worked with the anatomist Marcantonio della Torre and is estimated to have dissected over 30 corpses, with over 750 of his anatomical studies remaining today.[3]

This growing interest in observing the human form culminated in one of the most influential books in the history of medicine: the anatomical treatise De humani corporis fabrica, published by Andreas Vesalius in 1543. Why was this treatise revolutionary? First, it was obviously more accurate than the Medieval illustrations above:

Second, Vesalius’s treatise united art and science, changing the instruction of anatomy by using illustrations to demonstrate technical knowledge difficult to describe with text. This is one reason DaVinci’s sketches remain so arresting today; his illustrations are more accessible than even the best Latin translations.

But the biggest shock wave from De humani corporis fabrica was how it questioned existing beliefs primarily through practical experience and observation. Vesalius conducted dissections himself, formerly seen as an odious task delegated only to barber-surgeons. He held dissection demonstrations for hundreds of physicians and philosophers from all over Europe, where, instead of reading chapters from Galen and pointing as a barber-surgeon inexpertly hacked at a body, he himself both performed the delicate physical tasks and lectured on his observations. From these practical observations, his treatise controversially refuted over 200 errors of Galen which had held sway for over 1,300 years, such as imaginary organs present in ape skeletons, but not humans.[4] The drive to treat the human form as an object worthy of study in the natural world set a foundation for science to question established beliefs and seek knowledge through practice and observation.

[1] This is so cool! You can explore it all virtually at the Bodleian Library holdings.

[2] Keele, KD. “Leonardo DaVinci’s Influence on Renaissance Anatomy.” Medical History. 1964. Oct; 8(4):360-70.

[3] Jones R., “Leonardo da Vinci: anatomist.” British Journal of General Practice. 2012 June; 62 (599):319.

[4] Gumpert, Martin. “Vesalius: Discoverer of the Human Body.” Scientific American, Vol 178, No. 5 (May 1948), pp. 24-31.