Disentangling Drug Prices: What the heck is a PBM? (Part II)

A sticky sandwich between insurers and manufacturers

Why are drug prices so crazy? Last month we learned the layers of pharmaceutical distribution and how all the frosting- er, profit margins- pushes up prices. This month, we tackle one of these major layers: Pharmacy Benefit Managers

1. The rise of PBM: Pharmacy Benefit Managers

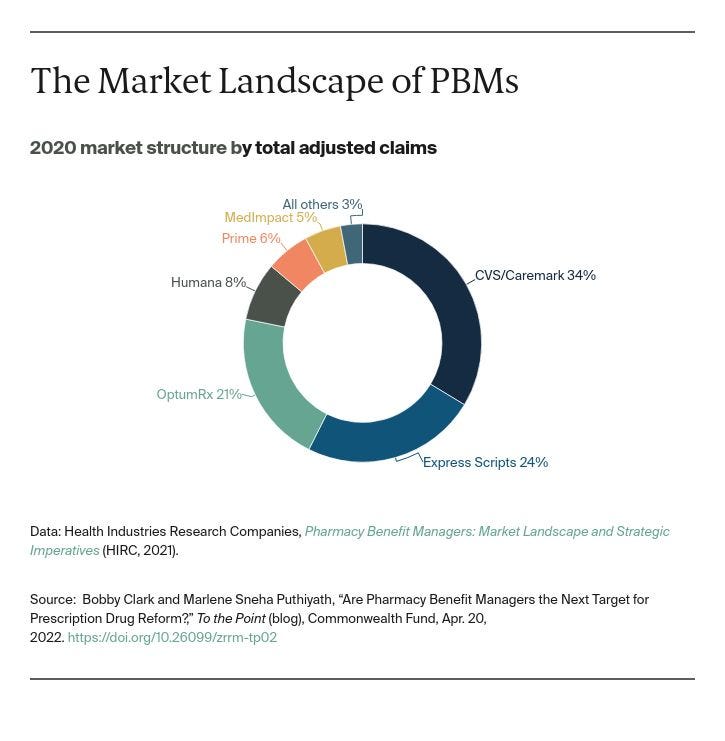

In 1970, 82 percent of drug costs were paid out-of-pocket, as drug coverage was not part of a standard insurance plan.[1] As pharmaceutical use ramped up, so did coverage, but this presented a new problem for insurers because it added negotiating with pharmacies and drug wholesalers on top of already managing networks for medical services. Enter the Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM), which serves as an intermediary for the insurance company for pharmaceutical products. PBMs never physically handle drugs, they instead negotiate between insurance plans, drug manufacturers, and pharmacies. PBMs also make up insurance plan formularies, or lists of pricing tiers for covered drugs, which heavily influences the final drug choices of enrollees. The most controversial and complex piece of what PBMs do is negotiating large, preferential, and varying rebates to manufacturers by drug type- essentially a promise to pay back some money off the “list price,” but only after enrollee purchase. The current large PBMs Caremark (CVS Health), ExpressScripts (Cigna), and OptumRx (United Health Group) control nearly 80% of the market.

PBMs have completely changed the pharmaceutical landscape. By 2012, only 18 percent of drug spending was out-of-pocket and over 95 percent of all prescriptions filled went through a PBM.

2. It all starts with good intentions…

PBMs in theory could generate big cost savings for the health care system. First, they can specialize in national-level drug pricing, releasing insurers to focus on local networks for provider care.

Second, PBM drug formularies can push greater use of generics away from expensive branded drugs by listing them in tiers with a lower copay.

Finally, in recent years, PBMs such as CVS Caremark announced a new focus on disease management. This means a high-level analysis of their populous, comprehensive databases on pharmaceutical spending to determine cost-effective methods for treating diseases with intensive drug use. For example, diabetes is a chronic high-cost illness with treatments that rely on a wide range of pharmaceutical products, from insulin to maintenance pills. PBMs can analyze pharmaceutical use with factors such as quality of care and patient compliance to understand cost-effectiveness of current treatment processes. These cost-effectiveness estimates inform which drugs to include in a formulary versus which to steer patients away from using.[2]

3. Ooey, gooey PBJ PBM

However, as drug spending and prices rise, the outsize role of the PBM is coming into question. In particular, the role of rebates in these transactions is both large and shrouded in mystery- sometimes legally binding mystery crafted by the PBMs themselves. Why do we care about this?

First, these aren’t those $20 off your big screen TV rebates, maybe not worth mailing in. Negotiated rebates back to the manufacturer can be as large as 40% of the listed price of a drug. With so much discount sloshing around, who’s getting these savings? PBMs report they pass along a large share to the insurer, and thus enrollees, but small plans and employers don’t agree. Why can’t they prove it? Drug-specific rebates are legally confidential between the PBM and the manufacturer, so the other agents in the transaction have limited ability to assess how much money changed hands. In fact, PBMs sometimes issue literal gag clauses, which prohibit pharmacists from telling a customer that they could find the pharmaceutical product elsewhere for cheaper.

Finally, all these secretive rebates obscure real transaction prices, not only for the consumer but for another major player: Medicare and Medicaid. Public insurance pays for drugs based on a fixed universal discount of the (now distorted and totally bogus) list price. Since rebates are merely a percentage paid back later, this cheaper transaction price is not reflected in the list price faced by government buyers, leading to higher drug spending for a major component of the federal budget.

What a gooey, sticky mess sandwiched between insurers and pharmaceutical producers! Tune into the next two lessons when we discuss ideas to clean things up.

As always, keep me updated on what you’re up to or reach out to chat with me about these issues!

Best,

TMD

[1] Getzen, Thomas E. “Pharmaceuticals” Chapter 11, Health Economics and Financing 5th edition. p237

[2] Seeley, Elizabeth, and Aaron S. Kesselheim. “Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Practices, Controversies, and What Lies Ahead” The Commonweath Fund, Issue Briefs, March 26, 2019.

Also check out the Department of Justice briefing.