Why is healthcare different than a pair of jeans? Part I: The consumers

Three ways consumers diverge from the ordinary in healthcare

Q: Why is healthcare different than a pair of jeans?

A: Because in healthcare, the genes are on the inside!

You’re welcome. You may offer up a few, less punny, ways that buying jeans differs from visiting your doctor, several of which may be complex or frustrating rather than funny. To improve our healthcare system, we need to know which frustrations stem from bad policy and which are something fundamental to consuming healthcare versus jeans. How does producing and consuming healthcare work differently than ordinary parts of the economy? First, the consumers themselves are different:

1. Time plays an outsize role.

Heart attack, car accident, seizure, and arthroscopic knee surgery. Which of these things is not like the other? Heart attacks, car accidents, and seizures usually don’t happen on a convenient schedule. They are unexpected, sudden, and severe. In these cases, people don’t have the time or mental ability to search for the least expensive care or even choose where the care is performed. An emergency call brings an ambulance; you go where you’re taken and say yes to whatever keeps you or your loved one alive.

Arthroscopic knee surgery is more like jeans shopping. You have this nagging feeling you’ll need it soon, so you ask your friends for recommendations, schedule a time to take care of it, and maybe even price compare.

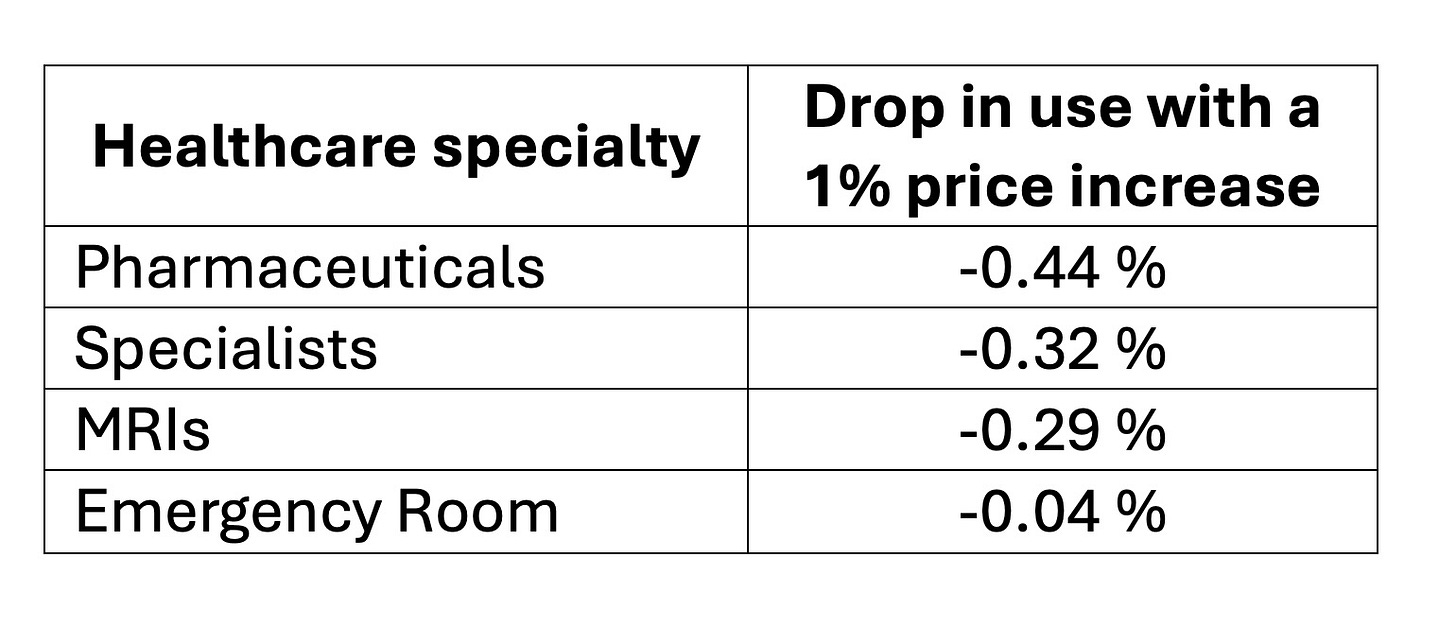

We can see this in the data. Economists measure how patients respond to price changes by something called elasticity.1 Essentially, if price increases by 1%, how much do patients reduce their spending? If consumers run away screaming, this is “pretty responsive.” For example, the St. Louis Fed estimated that a 1% increase in the prices of women’s clothing in 2008-2009 led to a disproportionately large 8% drop in purchases- falling 8 times faster than price increased.2 If purchases fall more slowly than price rises, this is “not so responsive.” This is most healthcare purchases. The chart below shows how consumption responds to a 1% price increase for various medical specialties. Pharmaceutical purchases drop at about half the speed of price increases, at -0.44 %. However, ER visits, where time is a key factor, the drop in use is -0.04 %. That’s pretty close to “no response.”

In my own research, I’ve found that patient response to price dulls as healthcare expenses pile up. In the range of $500-$750 of yearly spending, spending decreases only -0.26 percent for a 1% price increase. As small as this is, when I estimated reactions to price increases in the $1,250 to $1,500 range- where health conditions are more serious- the response dropped to a barely-noticable -0.09%.3 Most types of healthcare cannot rely on prices to influence patient choice the same way that ordinary consumer products can.

2. We don’t know what to buy!

While my fashion sense might not always be spot on (my friends label it ‘kooky chic’), I’m probably doing better than I would at neurosurgery. The average training time for a primary care physician includes 4 years of undergraduate education, plus 4 years of medical school, and then a 3-year residency program. Advanced specialization could add up to 4 years after those 11.4 Non-physicians simply are not armed with equal understanding when choosing medical services. As a result, we don’t even know what it is we need to buy.

Healthcare might not be the only area where you’re not a specialist. Cars are complex, so is wine, and I can’t cobble my own shoes. What helps me with these products is that I get another chance if I make a poor choice. All these purchases are repeatable, so you can learn about fit or quality. For cars, you can even learn about quality from other people’s purchases, since a car’s value is similar across individuals. Healthcare purchases like cancer treatments or ER visits are (hopefully) rare, non-repeated experiences. Markets for these types of medical services are missing the beneficial influence of repeated, informed customers who search out superior products.

3. The consumers are also the producers.

The real “thing” we are hoping to buy when we purchase medical care is not flu tests, heart stents, or chemotherapy. We are hoping to buy “health.” Medical care is an input to better health, but this input often needs you, the consumer, to share a role as producer. The efficacy of pharmaceuticals depends on the patient’s adherence rate, how well they remember to take their medications. Physical therapy prescribes consistent at-home exercises. Because the consumer of healthcare is also a producer, healthcare delivery requires greater levels of shared information, better communication, and mechanisms to check the patient’s understanding of their “purchase.”

The preceding discussions put consumers in a weaker spot when choosing healthcare than when choosing jeans. The bright spot for healthcare consumers over fashion consumers is that you are not solely relegated to that role. Informed patients jointly create better outcomes. Our good decisions on exercise, nutrition, sleep, and stress all improve the ultimate quality of healthcare expenditures. Not only should this empower the individual, this should lead us in rethinking the system- not as a healthcare delivery system like another Amazon dropoff- but as a network where both the patient and producer influence value, efficiency, and quality.

Next month, we’ll tackle the differences of healthcare as a product. Until then, my international readers- do you reap rewards for being a good patient and improving your health outcomes? Please share! U.S. readers, what policies do you wish rewarded you?

How easily can healthcare stretch? On the producer side, here’s some statistics on how inelastic hospital care was during the pandemic, hindering our abilities to ramp up healthcare quickly.

Econ 101 folks, practice your calculations of this very elasticity with the St. Louis Fed here! Midterm I is at 9am today, by the way.

Read all about it: Christina M. Dalton, “Estimating demand elasticities using nonlinear pricing,” International Journal of Industrial Organization, Volume 37, 2014, Pages 178-191,

Murphy, Brennan, “Medical specialty choice: Should residency training length matter?” American Medical Association. Nov. 19, 2020.

Thank you for bringing up such an important idea. As a doctor, it can be frustrating when many patients bring with them a consumer mindset. It does not serve them well. Even though patients may understand that a surgeon has a long waiting list for surgery and appointments, some will act as though doctors should “compete” for their business by adjusting recommendations as though I’m trying to sell them a TV. Moreover, many patients mistreat front-office staff as though they are hotel staff whose purpose is to serve them as “guests.” Broken markets and an inattention to how quality is measured versus perceived allows stakeholders to extract short-term profit by hijacking this consumer mindset.