In Part I and Part II, we documented many ways health enters our lives, including as an input to production and leisure. But what about the absence of health? Today, we bring our new understanding of health as an economic good to bear on one of the decade’s most pressing public health issues: obesity.

1. Obesity doesn’t pay

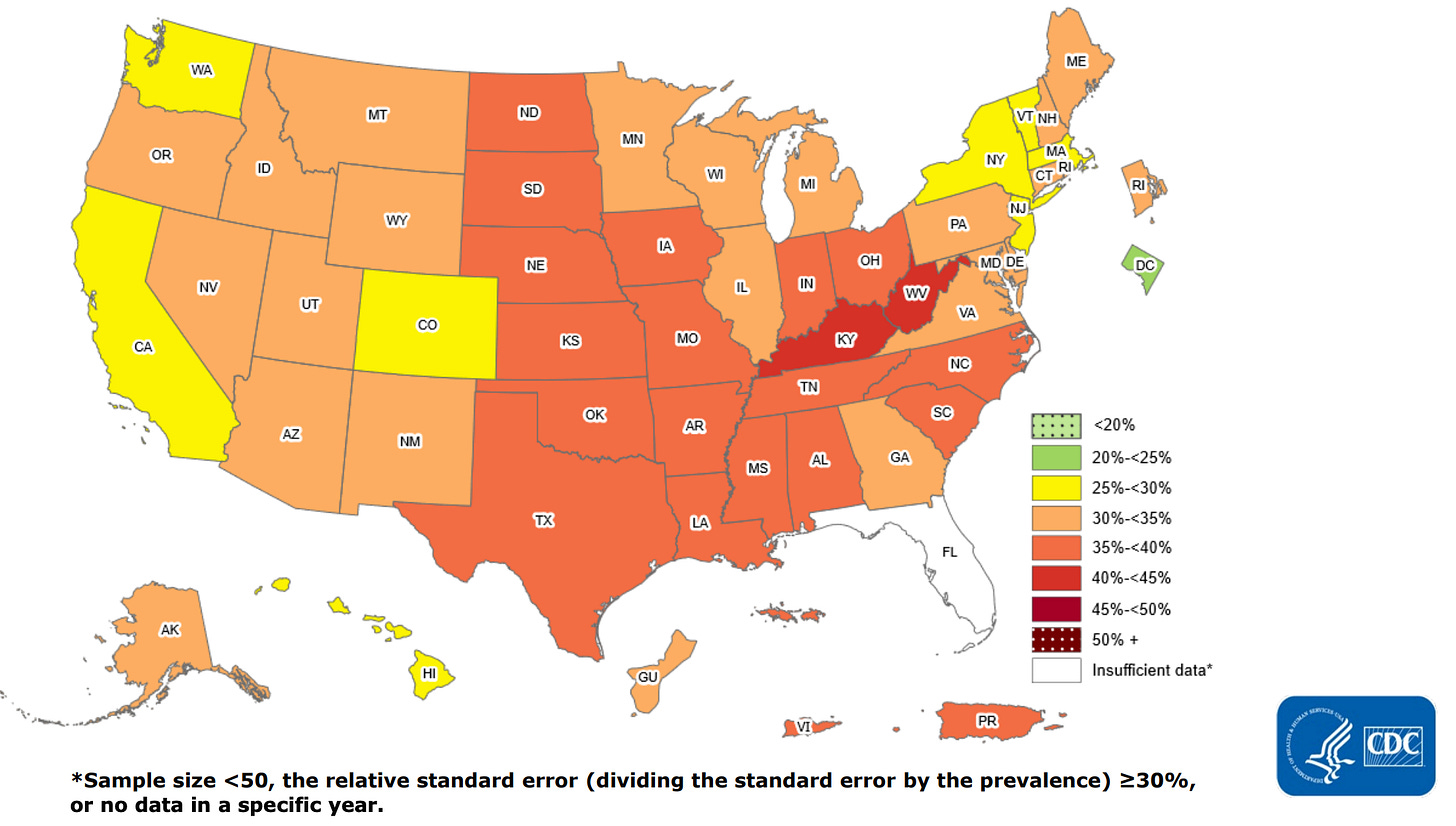

The latest CDC estimates from the 2017 to 2020 period list U.S. obesity prevalence at over 41 percent, up nearly 10 percentage points from 20 years ago.[1] These extra costs are burdening the health care system to an (estimated) tune of nearly $173 billion dollars a year and medical costs for obese individuals are, on average, $1,861 higher than medical costs for people with healthy weight.

However, since health is a tool in a greater economic system, the absence of health, through obesity, reduces its ability to be used as an input to production. The academic literature shows ample evidence of a wage gap between healthy and obese workers. Studies have found that a 1-unit increase in BMI leads to 1.8% fewer years employed, decreased chances of an interview callback, and an even greater impact on wages, as high as 2-3 percent for a 10% increase in BMI.[2],[3]

These studies grapple with whether this is due to decreased productivity—poor health capital may produce lower quality outputs—or discrimination—where perception of poor health capital plays a role. Alternatively, these lower wages may simply pass the higher health costs of an obese individual directly to the employee.[4]

This being established, these studies do not examine this gap over time. In Part I, we saw a precipitous drop in the need for good health capital on the job as our economy becomes less labor intensive. Let’s ponder that as we consider the other use of our health capital…leisure.

2. Leisure’s getting easier

The Bureau of Labor Statistics keeps a survey on how Americans spend their time.[5] On an average day in 2021, nearly everyone aged 15 and over engaged in some sort of leisure and sport activity, such as watching TV, socializing, or exercising, somewhere near 5 hours of their day. 20 percent of women, and 23 percent of men used this leisure time for “sports, exercise, or recreation,” usually a little over an hour if they did. “Socializing and communicating” was slightly more common- the overall average was 34 minutes.

A newer entry into our leisure time, playing games and using a computer for leisure now matches socializing, at approximately 34 minutes per day. But the biggest use of American’s time on an average day was watching T.V., at nearly 3 hours a day. Nearly 60 percent of our leisure hours engaged in an activity that has little to no use of our health capital stock- neither physical nor mental.

Compare this with popular activities of the 1950s: dancing, games, and the newly emerging hobby boom. Television was also becoming popular, but most of that list involves tapping into physical or mental health capital. Layer on to this the staggering increase in breadth and production quality of online entertainment in the past 10 years, social media stepping in as “socializing,” and we’re left with dwindling need for health capital in our leisure time as well

3. Tina’s comprehensive theory of obesity

In the face of both these trends, what else should we expect for maintenance of our health capital? Maintaining health remains costly- nothing has changed about the need for consistent exercise and self-discipline against increasingly available unhealthy foods. But the benefits of this expensive health capital are declining. Good health capital is no longer imperative to either earn income nor for employing much of our free time.

I believe a simple explanation for the rise of obesity is there are fewer and fewer external benefits requiring it, yet the costs of maintenance are still around. This holds true for the bleeding of obesity into developing nations, as their economic structure and standards of living rise to match the U.S. It also reveals why the problem is so persistent and rising despite much wringing of hands and hitting it from all sides—both work and leisure activities are relentlessly becoming less taxing to our health capital. Any solution to obesity must address this fundamental change in the value of health capital to the individual.

There’re perhaps reasons to be glad our health capital is less abused, since Part I also laid out that our increasing lifespans leave us in better health longer, an increase in quantity of health. The next avenue to influence might now be quality. Even though it is used less intensively, higher quality health makes us more productive on the job and we can focus on diverting those lingering non-TV hours into recreational and social activities that rely more heavily on high quality health.

As always, keep me updated on what you’re up to or reach out to chat with me about these issues!

Best,

TMD

Head back to Part I, “Taking Stock” or Part II, “Looking over Time and Geography.” Continue with Part IV, “A Great Resale Product.”

[1] Centers for Disease Control. “Adult Obesity Facts.” May 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

[2] John Cawley, “An economy of scales: A selective review of obesity's economic causes, consequences, and solutions”, Journal of Health Economics, Volume 43, 2015, Pages 244-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.001.

[3] Böckerman , Petri et al., “The effect of weight on labor market outcomes: An application of genetic instrumental variables”. Journal of Health Economics Vol 21, September 2018 https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3828

[4] James Bailey, “Who pays for obesity? Evidence from health insurance benefit mandates”, Economics Letters, Volume 121, Issue 2, 2013, Pages 287-289,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.08.029.

[5] Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Economic News Release: American Time Use Survey.” June 23, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.nr0.htm