Insurance: Why Does it (Really) Exist? (Part I)

A common answer might be, “because health care costs a lot! Let’s look deeper...

1. The fundamentals of why we want insurance are uncertainty and cost.

Uncertainty means we can’t be sure of the if and when we will get sick. Cost is how expensive it will be. We only need insurance if both of these factors are in play. Think about it. Do you have insurance for your monthly rent? Sadly, your landlord is going to ask for it with aggravating predictability! This cost, although expensive, is not uncertain. On the other end, catching a common cold is unpredictable, but usually not expensive. Insurance is really for events like cancer- hard to predict and extremely expensive.

In fact, uncertainty is what undergirds the whole insurance market coming into existence. To understand this, I invite you to step into my family for a minute, posing as my nephew. My sister-in-law, Gina, is a very fun and organized gal. She always remembers her nephews’ birthdays and finds a lovely gift. Now there’s me. I’m a scatterbrained professor, of course. Sometimes think of a super fun gift, and sometimes your birthday flies by me and you get nothing. Which aunt will be your favorite? If you said Gina, the gracious, consistent gift-giver, this means you don’t like uncertainty! Most economic surveys find that people don’t like uncertainty in most parts of their life.

Here’s where insurance steps in. At an individual level, which year we get the flu is hard to predict. However, at a population-wide level, the number of people getting the flu each winter is easier to predict. When an insurer covers a large population, the difficulty of predicting an individual outcome is replaced with the ease of planning for the group outcome. Insurance can collect individual premiums equal to total expected costs and pay out only to the individual who gets sick. The individual that hates uncertainty—even if she never gets sick—benefits from this arrangement because insurance has removed the uncertainty—costs are covered if this event happens. Insurance is based on uncertainty, not just cost.

2. Sure, but I don’t like paying for stuff! Why not just throw it all in?

Insurance mandates are like barnacles, hard to get off once they’ve latched on and create lots of drag.* Adding services into insurance that don’t satisfy both uncertainty and cost properties creates drag on the healthcare system and increases prices in two ways. How?

First, people care less about health care prices when insurance is footing much of the bill. This is called moral hazard. In essence, people end up purchasing more care or don’t “price shop” for care if insurance is insulating them from the true overall cost. Unfortunately, health care pricers understand this too; consumers don’t care, so producers increase their prices, out-of-pocket expenses increase, and we’re in an endless upward cycle. (Watch more on moral hazard here) Secondly, this moves services out of competitive markets (i.e., nice price competition to keep prices low) into the highly concentrated health care markets (i.e., hello monopoly pricing!).

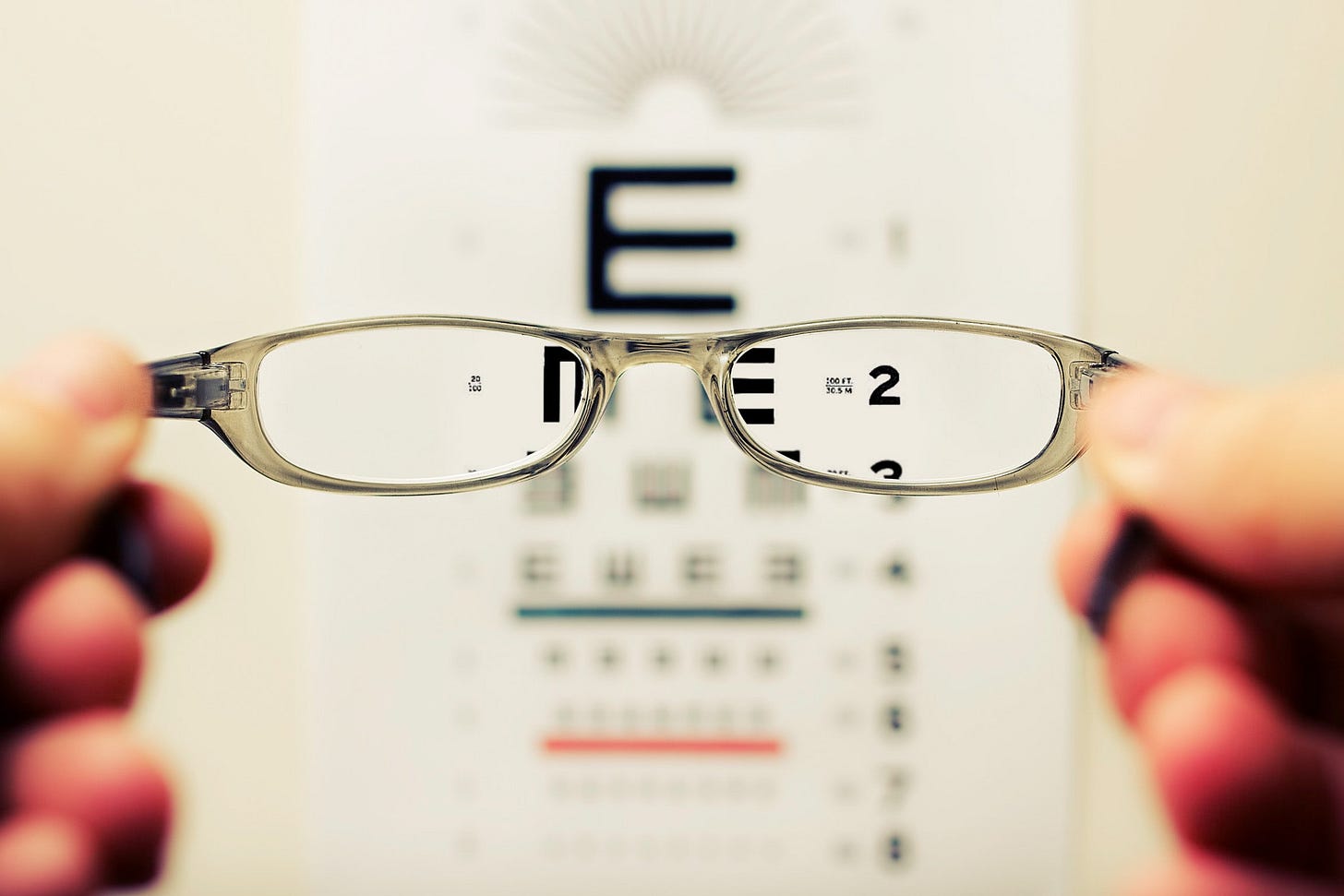

Think about eyeglasses. Even if they weren’t a geek-mandatory accessory, I’ve had glasses since I was 10 (or maybe I’ve just been a geek since then). This is not an uncertain purchase for me year over year. However, if I have vision insurance, I never see the price because I just pay my premium and it’s covered! When purchasing my latest pair I did not have this coverage, and the eye care center where I purchased the pair had TWO prices- for purchasing with insurance and for purchasing without. Guess which was higher? Yep, the price- for the same pair- was cheaper without insurance.

(Not to mention this all creates confusion by putting another player between the consumer and the producer. Check out Google reviews on your local eye care center and see how many people are complaining about inconsistent prices. This usually isn’t the eye care center, it’s because insurance coverage is hard to understand coupled with no one being able to get an accurate price quote from their insurer.)

3. A side note on why health insurance may be a different beast.

Compared to its colleagues of auto and home insurance, the timeframe to consider for cost and uncertainty of health insurance may differ. We can replace our car with a more reliable one or move out of a fixer-upper, but “vehicle” choice is sadly not an option in health! Are we interested in insurance for this year’s uncertainty (a car accident)? Or over a lifetime (mid-life cancer diagnosis)? Current health insurance markets focus on short-term, but a better contract might be for decades of coverage.

Consider Type I diabetes. Distinct from Type II, this is a chronic metabolic disease affecting approximately 1.6. million Americans[1] where the pancreas no longer produces necessary insulin. This creates a life-long need for daily blood glucose monitoring and insulin injections and eventually leads to other (expensive) interventions from a lifetime of increased stress on the circulatory system. Sometimes called “juvenile” diabetes because of its common onset in children, its causes are currently largely a mystery, meaning prevention is not a conscious choice.

The fundamental role of insurance is to protect an enrollee from expensive, but uncertain events. In the current market-based U.S. system, plans are chosen on a yearly basis, with new enrollment periods each year. In the case of Type I diabetes, there is no uncertainty for a bulk of yearly medical needs—glucose testing equipment and several daily injections of insulin, for which patient demand is highly inelastic. Leaving aside issues of high price levels or non-routine care, does the lack of uncertainty mean these patients have no need for insurance? These patients have routine high costs, but not uncertainty in these costs. In this case, the uncertainty exists at over a more expansive time period—beginning around onset age in childhood and going well into middle age. The pressing question is “will I contract Type I diabetes during my lifetime and face these costs over many years?”

A more relevant question is then, “what is the time period over which we would like insurance?” The “veil of ignorance” paradigm is a philosophical question which asks, “You can’t control your genetics or where you’ll be born. What system you would prefer to be in place before you’re born and find out your health characteristics?” Since you don’t know your draw ahead of time, you’d prefer that any person who gets the unlucky bad health outcome to be well taken care of. Under the veil of ignorance, an average person would like insurance over long periods of their life, not just a year. A better insurance contract would be one that controls for uncertainty over large periods of life, not merely the within-year shocks.

_______

* Regarding barnacles: They are also likely to infect other systems they come in contact with. Much like new minimum coverage mandates being increased over time! I’m really hitting my stride on this comparison. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration states “Large barnacle colonies cause ships to drag and burn more fuel, leading to significant economic and environmental costs” (https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/barnacles.html). Sounds like a heavy health care cost burden to me!

____

For more detail, ponder the fundamentals of uncertainty and insurance in this video.

As always, keep me updated on what you’re up to or reach out to chat with me about these issues!

Best,

TMD

[1] American Diabetes Association. “Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017,” Diabetes Care March 2018.

Read the rest of the insurance series: Insurer's Perspective (Part II), Incentives (Part III), Rising Costs (Part IV)