Last week, I gave a talk to members of the Leader’s Board, which brings together leaders from major healthcare systems across the U.S. This meeting in particular focused on something called “value-based care,” a model which rewards providers for quality outcomes, patient experience, and cost efficiency rather than simply payments for services performed.[1] This kind of care delivery system has been growing since the 2010s, spurred by new Medicare incentives sharing cost-savings between CMS and providers. But to organize healthcare around value, we must wrestle with “What is value in healthcare?”

From an economic standpoint, value is simply the benefit you receive from a good or service. The tricky part of this definition is that value varies by “you”- the preferences and priorities of the recipient, and healthcare has a wide variety of stakeholders.

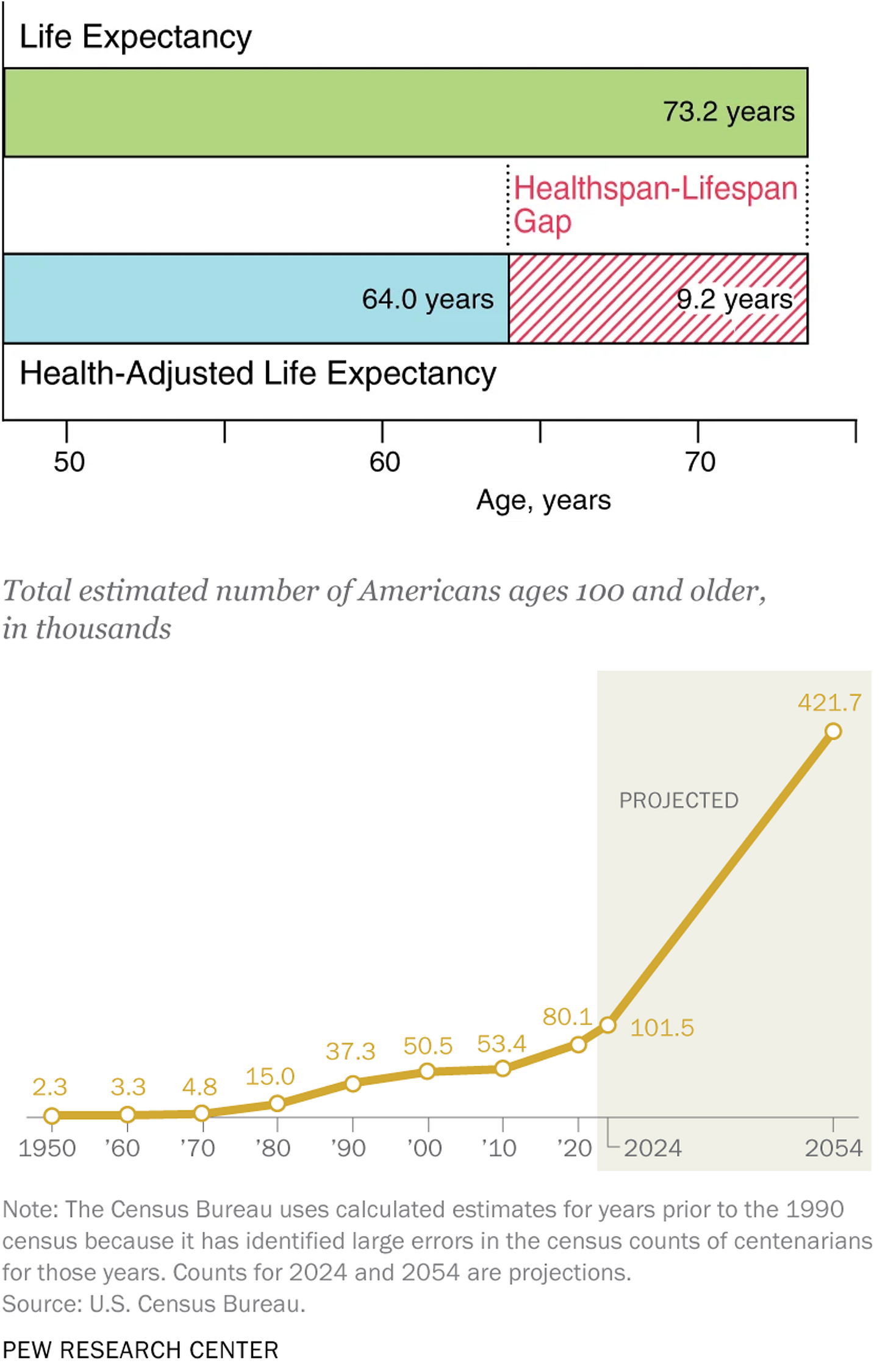

From a patient’s perspective, is value a longer life expectancy? Recently, attention has shifted from lifespan, the total number of years of life, towards healthspan- the number of years spent in good health. High-value care should aim not just to increase how long we live, but how long we can do what we love and maintain independence.

In 1980, healthcare was 9 percent of GDP; by 2024, it has climbed to over 17 percent.[2] Reducing costs is another key driver of value, but what are all the costs? From an economic perspective, costs are more than just hospital balance sheets. Economists have invisible hands; we can also see ‘invisible’ costs!

What are these ‘invisible’ costs? Inefficient care creates unnecessary or wasteful spending. Poor care coordination or low impact treatments both inflate costs and worsen health outcomes. For example, a recent JAMA study estimated accountable care coordination, such as programs managing patients after emergency department visits, could save 29.6-38.2 billion to healthcare systems. More efficient care prevents future acute emergencies and staves off chronic conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes, both in the top 10 causes of death in the U.S.[3]

Rising costs lead to rising prices, but prices can be invisible too. I’ve previously discussed healthcare’s failings in price transparency- the ability to view prices for services and shop for better prices. Improving tranparency would cut costs, but also improve quality by aligning the true costs of care with its benefits.

Another invisible price? Time. Patients “pay” in time searching for providers, waiting for care, and in recovery. Within healthcare systems, allocating providers’ time to high impact areas also improves value. For example, intensive care units were so overwhelmed during COVID-19 that providers such as cardiologists had to be switched into ICU units. While cardiologists are undeniably competent providers, they are trained to have the highest impact in their own domain. Diverting of provider time partially contributed to increased heart disease mortality through delayed and cancelled appointments.[4]

Finally, invisible in accounting statements, but not to patients: healthcare is confusing! “Health literacy” measures ability to read and understand prescriptions, relate lifestyle to health outcomes, or understand insurance and provider statements. In the US map below, green represents the highest areas of health literacy, while red shows the lowest. The ability of patients to understand and thus direct their own care varies widely, even within states.

The Leader’s Board members are taking on these invisible costs. Programs such as nurse navigators direct patients towards more efficient care paths by scheduling follow-up primary care visits after emergency department care. These nurses and pharmacy tech also reach out to patients to maximize the impact of care already prescribed, preventing future complications and reducing confusion. Finally, they use multidisciplinary teams including social and community health workers to improve the impact of provider’s time by matching medical problems to medical services but social problems with social services.

Value-based care isn’t just a shift in payment for health systems; it’s a fundamental rethinking of how to measure success in healthcare. By confronting these ‘invisible’ but real, costs, these systems are imagining a more effective and efficient healthcare landscape and hope to redefine what it means to deliver truly valuable healthcare.

If you’re interested in creating a more preventive-care focused system, check out my series asking Why isn’t our current healthcare system creating health?

[1] To understand the disadvantages of traditional payment systems, where payment only happens for services performed, check out how Medicare traditionally pays providers and How Insurance is like Costco.

[2] “National Health Expenditures; Aggregate and Per Capita Amounts, Annual Percent Change and Percent Distribution: Calendar Years 1960-2022.” National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Table 1.

[3] Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, “Leading Causes of Death, 2022.”

[4] Wadhera, R, Shen, C, Gondi, S. et al. Cardiovascular Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. JACC. 2021 Jan, 77 (2) 159–169.

Thank you for highlighting perhaps the central question of healthcare that needs an answer before proceeding with any additional steps. As you note, each stakeholder has a different answer to that question which understandably can be self-serving. I can't speak about everyone else but as a doctor, I want patients to be happy, their referring MDs to be happy and to avoid a malpractice lawsuit. So, to keep patients happy, I yield to their desires such as a desire to increase lifespan even with no healthspan (from the point of view of the patient when they are actually 80 and diseased rather than for a 50 year old policy wonk deciding for an 80 year old.) Referring MDs want you to solve the problem, not to punt the problem back to them. For some, it means MRIs and invasive treatments or at least an attempt to fix a problem even if the odds look statistically poor. Finally, to avoid lawsuits, it behooves me to overkill every chance at a diagnostic test because no one will fault you for being excessively careful. Payors will view these actions as "poor value." But if patients and caregivers view them as valuable, then what mechanism exists to resolve these points of view?

Also, it is worthwhile to note that in 1980, those over 65 constituted about 11% of the population, whereas it is now closer to 18%, a greater than 60% increase so there would be an expectation to take a greater proportion of the GDP if everything else remained the same. But everything else probably doesn't remain the same, i.e. new technologies, meds costs more out of proportion to inflation. United Healthcare, the largest private insurer, IPO'ed at $0.06 a share in 1984, and now trades at $615/share based presumably on anticipated net income.