In our last installment, we hit our last Medi-thingie: Medicaid.

1. What is it? Who and what does it cover?

Medicare targets the older end of the U.S. population, while Medicaid aims to aid the opposite end. The core target population for Medicaid is low-income families, pregnant women, and children. Unlike federally-funded and federally-run Medicare, Medicaid is only partially funded by the federal government. The remaining funding, and all design and implementation, comes at the state level. The Federal government determines minimum standards for who's covered and what's covered (a basic mix of inpatient, outpatient, and physician services), but states have freedom on how to administer this, as well as the option to cover a broader base of people (i.e., further from the Federal Poverty Line or including single adults) and/or cover more services (i.e., prescription drugs or dental services), if the state can swing it financially.

This is why your state's Medicaid structure might look slightly different than other states', and why there are so many creative riffs on names. Play the game below and see if you can guess what program goes to which state!

Check your Medicaid cleverness here!

2. Medicaid Brouhaha and the ACA

Medicaid has gotten tangled up in political ping-pong in the past few years because of its place in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Have you heard the phrase "Medicaid Expansion"? Medicaid became a hot button issue because of its keystone role in the originally-conceived blueprint of the ACA and its core mission to reduce levels of uninsured people in the U.S.

The U.S. stands out in a bad way among industrialized economies for its population without any health insurance coverage. In 2010, the year the ACA went into effect, nearly 20% of U.S. adults did not have health insurance coverage. (This is now closer to 12%). In contrast, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, and the U.K. all have universal health insurance coverage, that is, 0% of the population without insurance, even though these countries use different organizational structures and vary in use of public versus private insurance providers.[1] The overarching way the ACA tried to achieve this universal coverage goal was via the individual mandate-- making it a law that everyone had to buy insurance. Voila, problem solved! It's now illegal to not be insured.

Since that solution all by itself glossed over a few significant hurdles, such as "umm, buy where?," and seemed unfair for those without access to employer-sponsored insurance or low income individuals, the ACA simultaneously planned to increase purchasing options (by introducing the ACA Health Insurance Marketplaces) and increase subsidized coverage for low-income adults (by expanding Medicaid). Medicaid expansion was supposed to hold the ACA's mission together by opening Medicaid availability to those who couldn't afford insurance, thus enabling the individual mandate to be enforced across all incomes.

The hang-up comes from what we learned above. Unlike Medicare, Medicaid is funded and managed at a state level. The Supreme Court ruled that federal legislation did not have authority to direct states on how to administer their own programs. Even with short-term federal subsidies, some states balked at the jump in costs of Medicaid expansion as well as shouldering a larger burden of health risk. (Remember in Part I the additional tasks and risk that governments take on by providing insurance.)

Another reason why states might balk at expansion is the economic phenomenon called crowding out- where individuals switch from their existing private insurers into subsidized public sector services. This pushes ("crowds") private producers out of the market, not to mention increases the public tax burden. Studies have found expansions of public insurance can crowd-out between 25% to 50% of private market provision.[2] The bigger the crowd-out, the bigger waste of public resources that could be directed to better (non-duplicative) use.

You can find out if your state expanded Medicaid here.

3. Oregon Health Insurance Experiment

The super awesomest part about Medicaid's state-level implementation (well, if you're a health economist) is that the variety of approaches helps us study effective health insurance policy and enrollee behavior. Why is this a golden opportunity? Unlike studying health outcomes in the science of medicine, we don't usually get to do experiments in health economics. For example, let's see what happens if a pandemic hits the U.S. economy in 2020. Ok, now let's see 2020 again, please, but with no pandemic and compare. Less irreverently, insurance enrollment is usually a voluntary choice, not randomly assigned to an enrollee. This means insurance outcomes are irrevocably biased by the enrollee's reasons for choosing insurance. (Called adverse selection.)

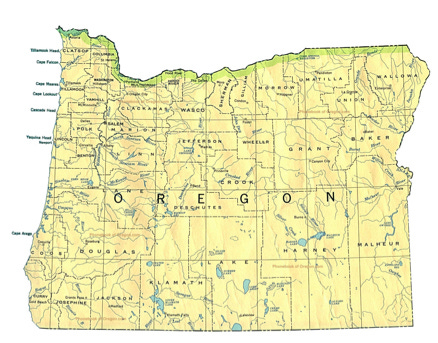

However, an amazing exception to this limitation arose in 2008 as the state of Oregon tried to expand its Medicaid program. They wanted to cover more single adults but didn't have enough funds to do this fully. To try and be fair, the program asked anyone wanting coverage to send in a postcard. All these postcards went into a huge metaphorical hat and (here's the magic) the program chose names to receive coverage at random. Like random assignment in an experiment!

The result is the largest experiment on insurance behaviors in U.S. history, called the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. The ongoing study tracks the effect of expanding public insurance on healthcare uses and health and financial outcomes of low-income adults. Early results showed that Medicaid coverage significantly increased doctor visits, hospitalizations, prescription drugs, and emergency department visits. Related to crowd-out, the study also found that households that newly received adult coverage were more likely to newly enroll a child in Medicaid, even though this child would already have been eligible. (This is sometimes called the "woodwork" effect, for coming out of the woodwork.). Unfortunately, there have been no short-run improvements in health outcomes, but the biggest punch of expansion was in relieving financial anxiety for enrollees.

Read more about the OHIE and its results here.

Read the rest of the Medicare series: Medicare vs. Medicaid (Part I), Medicare Advantage (Part II), Medicare Drug Plans (Part III)

[1] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/press-release/2021/new-international-study-us-health-system-ranks-last-among-11-countries-many

[2] Blewett, Lynn A., and Kathleen T. Call. "Revisiting Crowd-Out." The Synthesis Program Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 2007.