Health insurance produces more “WHYs?!” and frustrations than any other topic. Last time we asked, “Do insurers profit from keeping people healthy?” The answer is “much less than we’d like.” This begs the question:

“How do insurers make profit, anyway?”

To dazzle you with some advanced business education, remember profit is: Money In – Money Out. For a health insurance company, “Money In” is all the payments collected from their enrollees, such as premiums and coinsurance. “Money Out” includes expenses like administration, marketing, and taxes, but the big-ticket item is the potential health care expenses incurred by enrollees.

Insurance Profit =

Premiums x Number of enrollees (plus other out-of-pocket stuff like coinsurance)

- Expected Payouts for medical services (plus administration, marketing, taxes)

Profit increases by making “Money In” big and “Money Out” small. Let’s examine how this plays out for health insurance.

1. Make “Money In” BIG

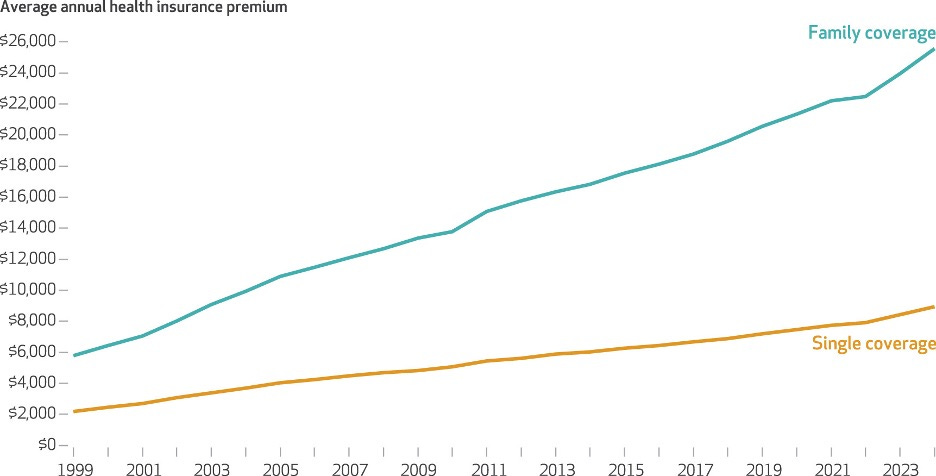

“Money In” has two parts. Premium choice is the most crucial part of a plan since these payments come in whether or not services are consumed. Copays and coinsurance are partial payments only when medical services are performed. The average 2024 health insurance premium in the Kaiser Family Foundation’s annual survey was $8,951 for single coverage and $25,572 for family coverage, a 52% increase since 2014.1 While high premiums reflect rising medical costs, there are several forces in insurance markets that contribute to high prices.

First, demand for health insurance is what we call inelastic, meaning consumers don’t reduce their buying much as prices rise.2 Insurance is largely a necessity as the primary way to access care in the U.S. (though it maybe shouldn’t be for some services!). Second, changing insurance plans is annoying—understanding new coverage rules, checking your providers are still in network—all of this keeps people from switching plans for creeping price increases. The capstone on both is that insurers are nearly always a monopoly in their local market. The annual American Medical Association survey found 95% of non-rural markets would be classified as “highly concentrated,” the highest level designated by the Department of Justice merger guidelines. In 89% of these non-rural insurance markets at least one insurer controls at least a third of the market. Monopoly power inevitably means higher prices and reduced access.3

2. The role of Enrollees

Speaking of monopolies, note “Money In” increases with more enrollees. But enrollees also show up on the “Money Out” side, and in more ways than you think. Yes, more enrollees means more “Money Out” medical services purchased, but more enrollees also improves the word Expected. What is this term?

Insurance markets exist because we don’t like that health needs are unpredictable. It is hard to predict if we’ll get an expensive cancer, uncertain if we’ll have a bad car accident. We’d like to smooth out the potential financial burden of this uncertainty. However, these risks are only uncertain on an individual basis. When we aggregate up to a large population, say 8.8 million members (Kaiser Permanente, 2023), the number of cancer cases is more predictable.4 Take the population-wide probability of cancer times 8.8 million people, and you’re going to be pretty close. When Kaiser can directly predict how many members will get cancer (though not who), it can plan for the expenses much more easily than an individual member. This is called expected payouts. The bigger the insurer, the more easily they can predict expected payouts, giving it a competitive advantage and improving the “Money Out” term. Bigger is better on both sides of the profit equation.

3. Make “Money Out” small

More enrollees make payouts less uncertain, but the payout costs are still large. One way to reduce payouts would be patients using less care, for example if they were healthier. The lack of elective healthcare use during 2020 caused financial losses for hospitals, but did lead to above average profits for healthcare insurers.5 Unfortunately, last month’s post laid out some structural features working against insurers benefitting from a healthier population. This leaves insurers with less desirable ways to reduce payouts. First, plans try to influence patient choice using networks and pre-authorization, pushing them into cheaper providers.6 Second, these networks and the monopoly status from above create bargaining power to squeeze reimbursement rates for providers and hospital systems.7 Finally, what particularly generates public furor, insurers try to control what services are consumed, by imposing things like step therapy- trying a cheaper treatment first- or denials for services deemed high cost but low value.

The public protests cry that the difference between “Money In” and “Money Out” is unfairly large for health insurers. The size of the gap may not be at the core of the complaint, but instead how consumers seem to have the short end of the stick on both sides of the equation- either monopoly power inflicts higher premiums or monopoly bargaining restricts services and choice. Bigger insurers make expenses more predictable, and thus theoretically could save costs, but smaller numbers than 8.8 million are still large numbers. Increasing competition in insurance markets is one way we could improve consumer welfare by hitting two sides of the equation.

Keep me updated on what you’re up to or spark more discussion in the comments!

Best, TMD

Claxton, Gary and Matthew Rae, Anthony Damico, Aubrey Winger, and Emma Wager, “Health Benefits In 2024: Higher Premiums Persist, Employer Strategies For GLP-1 Coverage And Family-Building Benefits” Health Affairs 2024 43:11, 1491-1501.

For discussion of inelastic supply, check out this post on hospital spending during the pandemic.

Guardado, José R. and Carol K. Kane. “Competition in Health Insurance: A comprehensive study of U.S. markets.” American Medical Association, Division of Economic and Health Policy Research, 2024 Update.

Statista, “Largest health insurance companies in U.S. 2023, by membership” Feb 19, 2024.

Shrivatsa, Ishira.”The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Health Insurers,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Chicago Fed Letter, No. 471, September 2022.

For more on this, explore my post on “The Method Behind the Make-You-Madness”

Scheffler, Richard M. and Daniel R. Arnold “Insurer Market Power Lowers Prices In Numerous Concentrated Provider Markets” Health Affairs 2017 36:9, 1539-1546.