Disentangling Drug Prices: What’s next? (Part IV)

Why price caps won't work and how to smash that layer cake

This is the last in our series taking bite out of the multi-tiered layer cake that is pharmaceutical pricing. As we’ve seen, it’s a gooey mess with the final price to consumers marked up at each layer. But what if we could remove a few layers? Today, what’s being tried to fix this: what’s promising and what to beware of.

1. If you can’t join ‘em, skip ‘em.

I ended the last lesson with a provocative question, “Should pharmaceuticals even be in insurance?” This is not an unreasonable query when we recall that insurance should protect us from uncertain and expensive events. Cancer should be in insurance coverage. However, we don’t need insurance for toilet paper, or diapers, or new shoes, or shampoo. Yes, all of these things you need, maybe even urgently! That’s not what’s at stake here. The key point is that none of them are uncertain. You can predict when you will need them. Also, there are plentiful competing manufacturers, and it’s easy to price shop for them. As a result, most of these are also not expensive.

Many drugs for chronic and common diagnoses are highly predictable and mass produced. Why not remove these from our layer cake entirely? Walmart did exactly that with its $4 Prescriptions Program. Walmart Pharmacy offers nearly 100 generic medications, most for $4. How does it make prices so low? It has deleted insurance and PBMs from the equation for these common, mass-produced drugs and sells directly to consumers.

2. Latest industry disruptors.

A few brash innovators have been making waves lately, trying to wrest power, and high costs, from the status quo. The first uses the simple insight from toilet paper above—that the ability to price shop keeps prices low. GoodRx is a crazy simple idea: type in your medication and see prices at a dozen competing pharmacies. Consumers can then head directly to the one that’s cheapest, or even investigate online delivery.

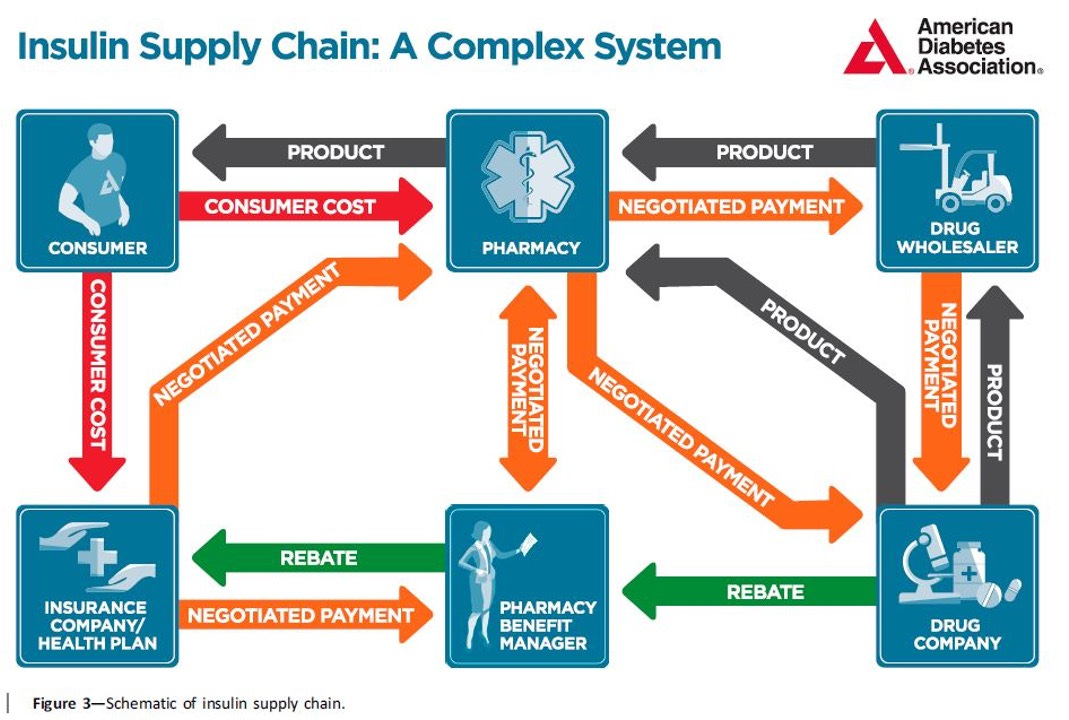

Headline grabbers of Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Pharmacy and Amazon Pharmacy are trying to experiment with cutting out PBMs and insurance. Cost Plus is partnering with a startup PBM outside of the top 3 which is focused on transparency. Amazon Pharmacy is focusing on what it does best, streamlining distribution. Recall the supply chain figure from Part I below. If the Insurance and PBM squares were deleted, so would be the in-back-over-under-through orange and green arrows of price mark ups and private discounting negotiations.

3. Why won’t price caps work?

One question we haven’t touched yet is, “if drug prices are crazy, can’t we just force them to be cheap?” This is the approach in the recent Inflation Reduction Act, in a small add-on regarding insulin. For Medicare patients, monthly insulin copayments are now capped at $35, and this has “encouraged” insulin manufacturers, such as Eli Lilly, to lower their list prices. While this seems good, I want to push harder on why simply announcing/legislating, “The price shall now be low!” doesn’t solve the problems we’ve been working through in this series.

Let’s illustrate with our aforementioned necessary of toilet paper. Remember in the pandemic, when you couldn’t find toilet paper or it was super expensive? Stores tried purchase limits and local media decried price gouging, but it didn’t do anything to get more, low price TP into the hands of customers. The holdup was that household demand had surged for those comfy, petite rolls in your powder room, but the existing supply was designed for corporate buyers: scratchy industrial-sized rolls. Grocery shelves didn’t fill, and prices didn’t return to normal, until manufacturing shifted to home use.

Back to insulin, U.S. prices are 5-10 times higher than other industrialized nations and it is harder to get than ever. However, over 90% of the U.S. market is dominated by only three manufacturers with little competition from generic or biosimilar products.[1] Even though most insulin is now off patent- some formulations have been around for 100 years-- manufacturers keep their market power through continually patenting new delivery systems. Think printer toner or razor blades. Each of these delivery systems are only approved to be used with their own branded insulin, effectively halting generic competition on the insulin product itself.

Legislating a $35 copay is a band aid fix like the picture above, limiting purchase quantities yet doing nothing to fill up the shelf. Better solutions are to dig deeper to open markets and expand competition to allow new drug products to fill our shelves.

As always, keep me updated on what you’re up to or reach out to chat with me about these issues!

Best,

TMD

[1] Ryan Knox, Insulin insulated: barriers to competition and affordability in the United States insulin market, Journal of Law and the Biosciences, Volume 7, Issue 1, January-June 2020.