Healthcare Goes to Prevention Camp! (Part III)

How can we create some happy, healthy campers?

In this series, we’re asking, “What holds healthcare back from optimizing health?” Modern healthcare systems emerged to solve acute, short-term problems, and did well at this. Now, our healthcare needs are increasingly long-term and chronic, with a vital preventive role for the patient. What would a better system look like? First, it should re-align current financial incentives which encourage overuse of medical care. Today, how to prevent costs in the first place by letting those who engage in prevention reap its benefits?

1. Playing hot potato with the couch potato

Chronic disease prevention has costs today—both money, time, and, sigh, effort—but benefits in the future. Modern insurance was designed for a short time-horizon. As a result, it separates these costs and benefits from each other. Most commercial contracts are for one year. The insurer pays for checkups, preventive tests, and medications this year, but there’s nothing keeping the patient in the plan next year. As a result, the costs borne by the first insurer may go squarely to help its competitor. I’ve written about this prisoner’s dilemma in insurance- where patients and insurers would be better off collectively rewarding prevention, but each insurer’s isolated incentives are against it.[1]

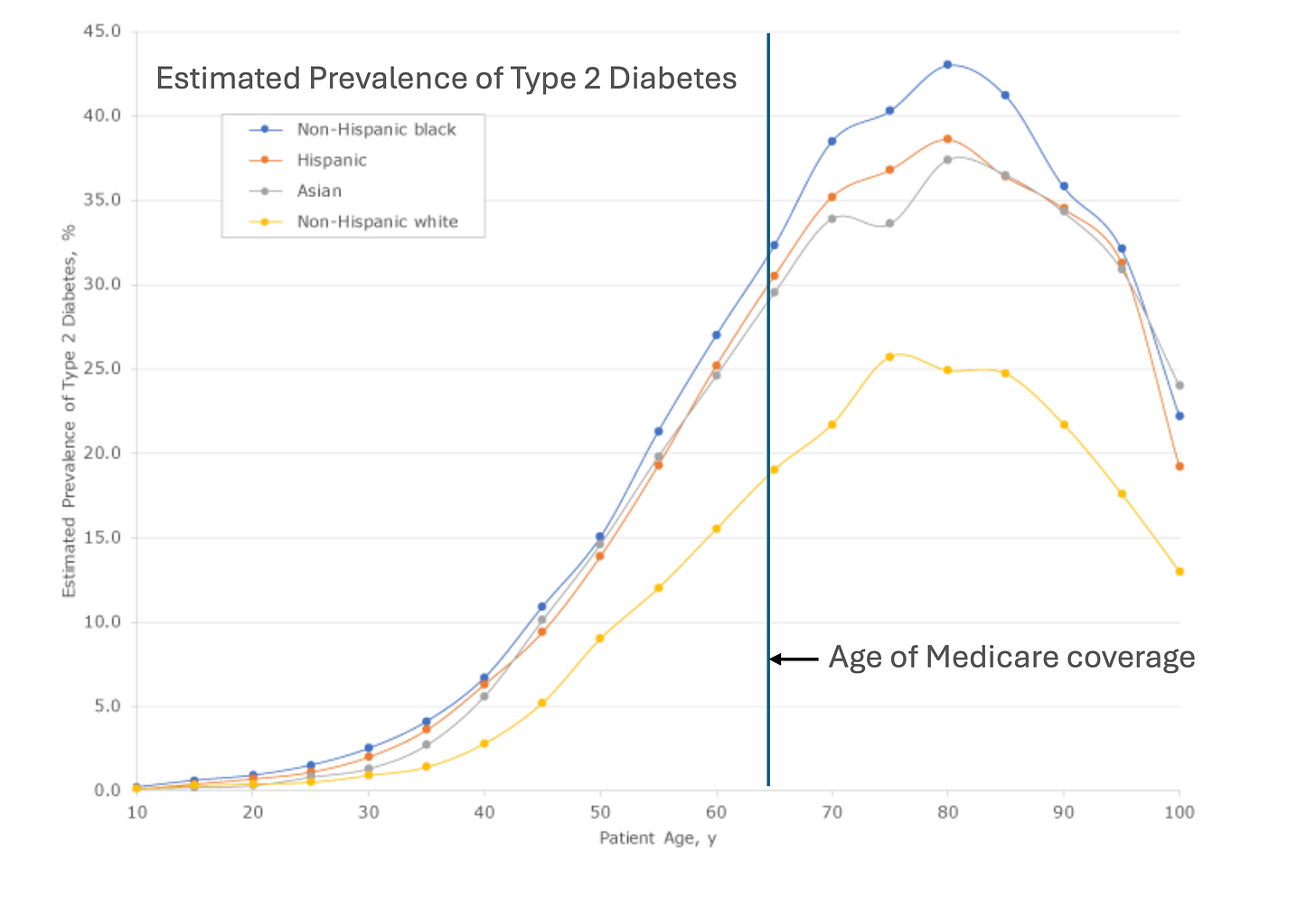

But hold on, let’s reverse that: Not preventing chronic disease is cheap today, but costly in the future. Someone must end up holding the hot potato, right? Patients may not engage in prevention and switch plans, but eventually that hot couch potato develops diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol and becomes very expensive. What happens when the music stops? Unfortunately, statistically speaking, Medicare sweeps in and ruins the game by taking those expensive problems out of the private sector’s hands. In 2017-2020, nearly 30 percent of those 65 and older had diabetes, and their per capita health care expenditures were roughly double every other adult age group.[2] The costs of preventing diabetes are in the hands of private insurance, yet the financial rewards of prevention fall mostly into the government’s budget. Why would the private sector invest in costly prevention if they can’t collect the reward?[3]

2. A lopsided tug-of-war for prevention

Besides Medicare, who else would benefit from less chronic disease? Unfortunately, not you, at least as much as you might like. Healthy lifestyles don’t pay you back as much as they used to- for either work or leisure. Jobs require less physical labor, and the rise of the internet means a whole new world of leisure is available from our couches.

In Part II, we discussed how medical markets, and thus profits, are highly concentrated. No big lobby benefits from you not getting cancer. No big lobby benefits from you not developing diabetes. But there is plenty of benefit if you end up these for the highly concentrated insulin manufacturers (a grand total of 3 in the US) or other pharmaceutical manufacturers.[4] If this was a tug-of-war for balanced health, we’re lopsided without a counterbalance of “Big Prevention” to “Big Health.”

3. We’ve left out a key player- you, the individual.

Preventing long-term chronic disease has a new player: you. But in the current system, individual-level inputs are not matched to individual-level benefits. Insurance premiums are priced on ‘community rating’, essentially one average price over all enrollees in a plan.[5] One plan, one price (but many individuals). While this was desirable from an overall equity standpoint, it creates problems in areas where prevention could improve outcomes. It dulls individual incentives for prevention because there is little to no effect of their efforts on premiums (with no effect being the most likely).[6]

How could we shift from insurance as sickness pre-payment, to systems which encourage and financially reward prevention? If you’re forced to pre-pay for a new engine block this blunts your incentives for oil changes (as well as diverts the cash flow to pay for them.). Who could financially benefit from prevention? Currently, insurance doesn’t give safe driver/ healthy living discounts, aside from smoking cessation and some weak results from workplace wellness plans.[7] What kind of system could align around our new set of health challenges, so those making costly investments for the future are connected to the payoffs? In this long-stay adventure camp called life, how can we get us some happy, healthy campers?

We’ll be debating this and more in our next installment. I want to hear your ideas and dreams- what would a world look like that encourages health? Leave them here:

I- plus some friends I’d like you to meet- discuss these ideas and more in my podcast episode: Imagine with Me! Elle Griffin and Healthcare of the Future ( with

of The Elysian).Check out Part I: Why isn’t our current healthcare creating health? and Part II: Tips to treat sclerois of your arteries, ahem, your healthcare system.

[1] Some recent initiatives to fight this include “value-based care” where providers are held responsible (usually financially) by insurers for quality indicators of their patients. For example, health systems are given higher payments if a certain percentage of their diabetic patients maintain low A1C or for high adherence rates (number of fillings) for medications. However, payments are often linked to consuming more care, such as more cancer screenings or yearly checkups. More care for the right patients is cost-saving but might not be overall if healthy patients are those most likely to comply with checkups.

[2] Centers for Disease Control, National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, Nov 29, 2023.

Emily D. Parker, Janice Lin, Troy Mahoney, Nwanneamaka Ume, Grace Yang, Robert A. Gabbay, Nuha A. ElSayed, Raveendhara R. Bannuru; Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2022. Diabetes Care 2 January 2024; 47 (1): 26–43.

[3] Note that the benefits of getting diabetes still accrue to the private sector. Although Medicare pays the costs, they are paying private sector firms for their pharmaceutical and medical treatments. The current systems requires the private sector to take on prevention costs where they won’t get benefit, but which will directly reduce future profits from treatment.

[4] Ryan Knox, Insulin insulated: barriers to competition and affordability in the United States insulin market, Journal of Law and the Biosciences, Volume 7, Issue 1, January-June 2020, lsaa061.

[5] This is true particularly post-ACA, which stopped the practice of pricing according to ‘pre-existing conditions’ in the market for individual plans. However, this community pricing was already the norm for most employer-sponsored insurance plans pre-ACA.

[6] The Kaiser Family Foundation reports in 2023 that average family premium has increased 22% since 2018 and 47% since 2013. KFF, “2023 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” Section 1 “The Cost of Health Insurance.”

[7] Two to check out: Song Z, Baicker K. Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(15):1491–1501. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3307; Reif J, Chan D, Jones D, Payne L, Molitor D. Effects of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health, Health Beliefs, and Medical Use: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):952–960. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1321

Excellent post and thought provoking! Can’t wait to read next week!